Interacting with Classes

When beginning Ruby, one often overlooked concept is how classes interact with each other. There are a lot of resources out there on creating your own class, but it always seems like the next step is a full blown app with multiple classes, modules and other miscellaneous files. All the excess content can distract a beginner from taking their knowledge on classes from A to Z.

An aspiring web developer might feel a tad overwhelmed. There needs to be smaller, more digestible steps in between creating your own class and creating that full blown app with all the bells and whistles.

That’s what this tutorial aims to do. Build a small program with multiple classes that helps you go from A to B instead. If you know how to create a class but don’t know what to do next. This is for you. Time to make these classes work together!

Fighter Class

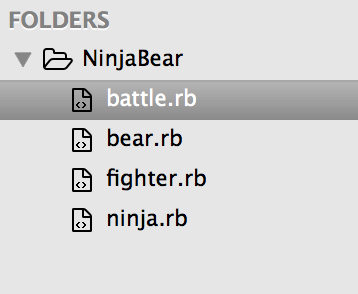

First let’s create a folder to store all of the files in our project. You can call it whatever you want, but I’m calling it NinjaBear. Now we will create a file inside of it called fighter.rb for our Fighter class. Up until now, you have probably been coding out your programs in one file but it’s time to ditch that for more modular code. We will separate each class in it’s own file.

Inside of fighter.rb let’s denote that we are making a Fighter class.

We are going to use this class as the parent of our two separate classes of fighters: Bears and Ninjas. By now you are probably aware that there is a special method used in classes called #initialize that executes whenever a new object is created from a class by calling the ::new method. The :: denotes that this is a class method.

We can put anything inside of #initialize, but it is very common to use it to set the values of the attributes in the class, like so:

Now, when we call Fighter.new, we can pass in the values we want to give a new fighter like this: Fighter.new('Muhammad Ali', 100, 20). However, if we want to be able to see the values that are stored inside of these variables, or manipulate them, we have to make them accessible to us.

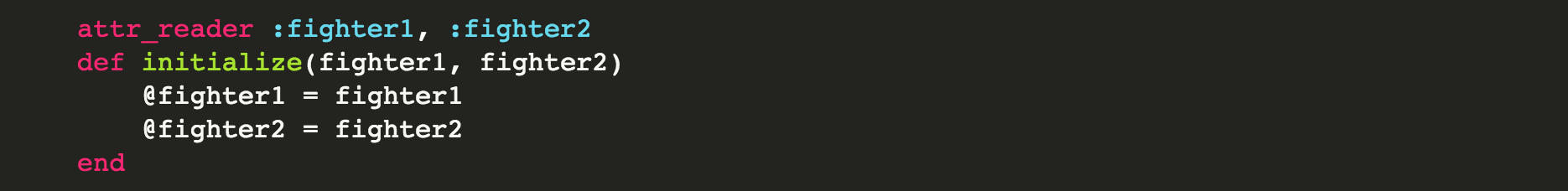

We can do this by adding in helpers that let us read, write, or both read and write attributes. Look at the following block of code.

attr_reader just allows us access to read or see what value is stored in our name attribute when we call it on an instance of the Fighter class. So, if we created a new fighter and stored it in a variable, f = Fighter.new('Rocky', 110, 15), we could now call .name on the variable, f.name, to access the value 'Rocky'. We chose attr_reader because we don’t have any need to change the fighter’s name after initializing him, only the ability to retrieve the value later, if necessary.

We use attr_accessor for health and power, because we want to be able to get the value contained in each attribute and also change the value later in our program.

Now that our attributes are set, we can give our fighter some functionality. Let’s give him the ability to attack another object. And, also the ability to lose health if he is attacked by another object.

Starting with the second method, a fighter can lose health by reassigning it’s own health variable to itself minus the power of the enemy or object that is attacking them.

The first method allows our fighter to pass in another object to attack, and then calls the #lose_health method on it’s enemy. This in turn causes the object passed in to lose health by the amount of power the fighter object has that attacked it.

Of course, these methods assume that the object being passed in is also a fighter, and it has the ability to lose health. Let’s check out our new methods by creating two objects from our Fighter class and calling the methods on them.

When we run this in our terminal we can see that the output is exactly as we expected and everything is working perfectly. When our first fighter attacks the second fighter, the second fighter loses his health by the amount of power the first fighter has, and vice versa.

leemccormick$ ruby fighter.rb

85

#<Fighter:0x007fa6428f00d0 @name="Muhammad Ali", @health=85, @power=20>

90

#<Fighter:0x007fa6428f0120 @name="Rocky", @health=90, @power=15>Bear Class

We are ready to move on to building our next class! Let’s create a file named bear.rb and use this to handle the code that deals with our Bear class. As stated earlier, the Bear class will inherit from the Fighter class. This means that it is able to use all of the same attributes and methods as the Fighter class, but can also modify the methods or add new attributes on top of the ones belonging to the parent class.

In this program a bear will be a type of fighter, and the other type of fighter will be a ninja. We display inheritance from another class like this:

And we can also use the #initialize method in our new Bear class. But instead of having to write out all of the same attributes again, we can just call the #super method to initialize a bear object with attributes from its parent, fighter.

To modify or extend the attack method from the Fighter class, we can simply redefine it in our Bear class. We will keep it the same, but add a small change, puts "RAWRR!!", that makes our bear roar when he attacks.

Ah! But if we run this inside of our terminal, something is wrong:

leemccormick$ ruby bear.rb

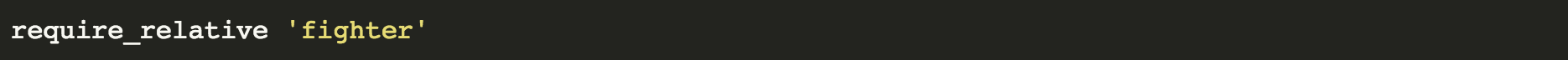

bear.rb:1:in `<main>': uninitialized constant Fighter (NameError)We get an error that our bear.rb file does not recognize the code in our Fighter class. Luckily, this is a very simple fix. All we need to do is add the helper method #require_relative, followed by the file name, to give this file access to our fighter.rb file.

require_relative 'fighter'

require_relative 'fighter'Here we use #require_relative instead of #requirebecause the files are contained in the same folder. When we use any of the require helper methods we don’t have to explicitly type out the extension on the file, only the name. These helper methods know automatically to look for files that work with Ruby.

Since our Bear class now has access to our Fighter class, let’s again check to see if our output is as expected when we call the methods and modified methods we created in both classes:

leemccormick$ ruby bear.rb

90

RAWRR!!

88

80

#<Bear:0x007fe41608fb18 @name="bear", @health=80, @power=12>

#<Fighter:0x007fe41608fac8 @name="ninja", @health=88, @power=10>Once again, our program is running perfectly. All methods still work and are able to access and change the attributes of another object. We can also see that the attack method in the Bear class prints out an additional “RAWRR!!” statement, exactly what we expected to see.

Ninja Class

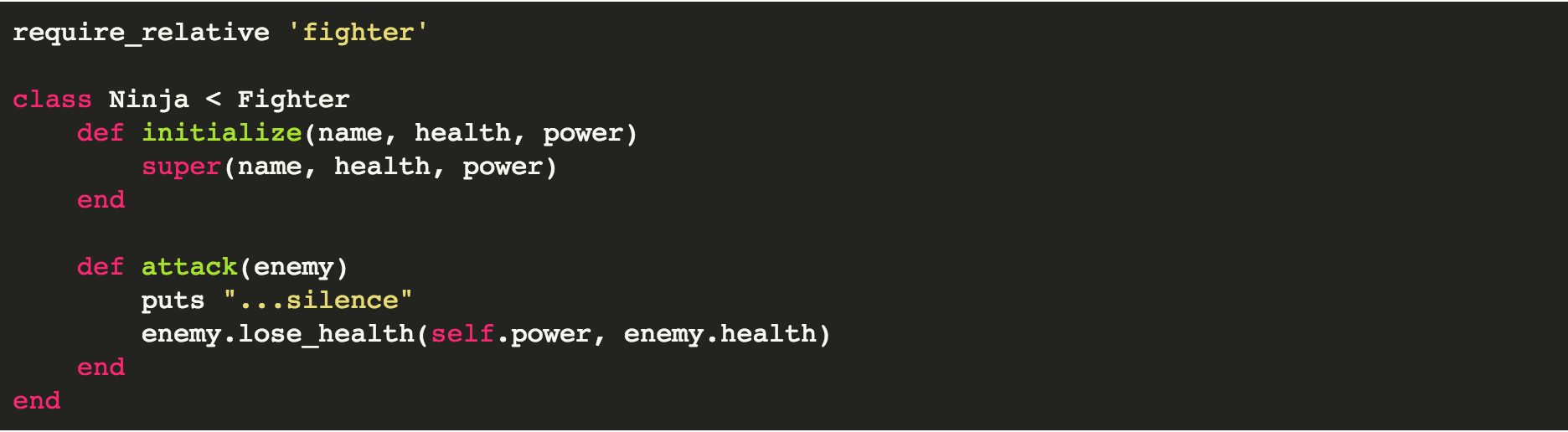

Let’s do the same thing with our Ninja class as we did with our Bear class. Create a file named ninja.rb.

For simplicity’s sake, we won’t make a ninja that much different from a bear. But we know that if we wanted to, we could make them drastically different. For now, we will just modify the attack method to print a “…silence” string, since ninjas are super stealthy.

Battle Class

It looks like our three classes are all ready to work together. Let’s create one more class called Battle and create it in a file named battle.rb. In this class we will tie all of our classes together.

Our final folder structure should look like this:

Just as we required the fighter.rb file in our bear.rb and ninja.rb files, we will need to do the same for any code we want to bring into our battle.rb file. Only this time, we only need to require the bear and ninja classes. This will also include the Fighter class indirectly, since both the bear and ninja classes include the Fighter class in their files.

We will set up our #initialize method to accept two different objects as attributes for the Battle class that will store two different fighters. The Battle class has no idea what type of objects these will be nor does it care. All it cares about is having values to store in its attribute variables upon initialization.

Again, in this instance we won’t need to change the fighters once they have entered battle, so we only need the attr_readerhelper method to allow us access to read the attribute values.

Let’s make sure that we are able to create a Bear object, a Ninja object, and a Battle object in this file. Then let’s access the bear and ninja object’s attributes through the Battleobject.

We can do this by using the following code:

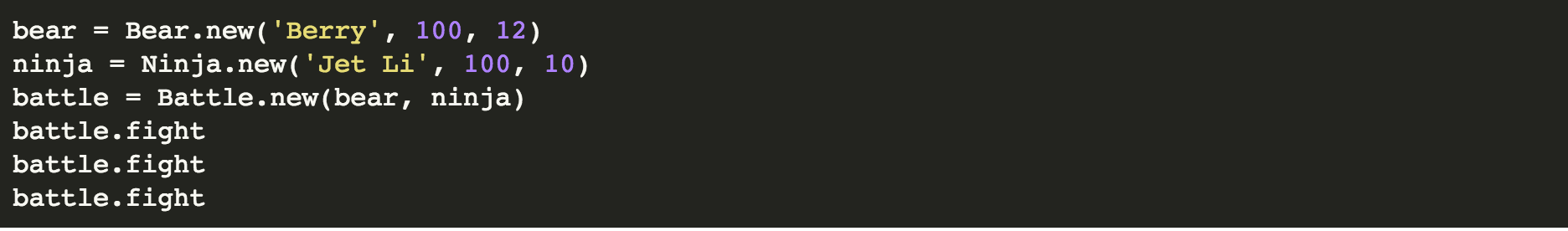

We created Bear and Ninja objects first and then passed them to the Battle object. The Bear object was stored as @fighter1 and the Ninja object was stored as @fighter2. Now both objects are stored as values inside of this new Battle’s attributes.

We access their individual attributes by first calling the attribute of battle that we want to access, and then calling the attribute of the Ninja or Bear object that we want.

leemccormick$ ruby battle.rb

Berry

Jet LiOur output gives us the values of the name attributes that are stored in our Bear and Ninja classes, yet we are still in the Battle class.

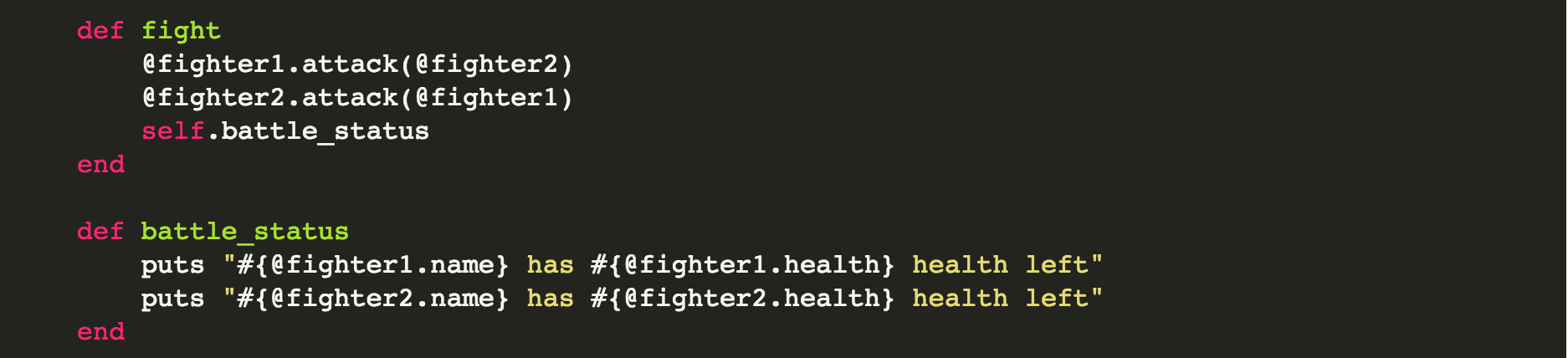

Let’s add some more functionality to our Battle class to allow our ninja and bear to duke it out, as every bear and ninja should. We will create two simple methods, one that uses the attack methods from the external classes and uses them inside of our #fight method. This method simulates a fight.

And the second method will check the status of our fighters by calling the external attributes on their respective objects that are being stored in the battle’s attributes.

def fight

def fight

Finally, let’s make sure everything is working the way we want by trying out our new methods:

leemccormick$ ruby battle.rb

RAWRR!!

...silence

Berry has 90 health left

Jet Li has 88 health left

RAWRR!!

...silence

Berry has 80 health left

Jet Li has 76 health left

RAWRR!!

...silence

Berry has 70 health left

Jet Li has 64 health leftVoila!! Our battle was able to incorporate all three classes inside of it to make our classes and objects interact with one another on a simple yet powerful level.

Stay tuned for the next installment of class interaction part 2, as we learn to make this program interactive with our user, and also how to incorporate modules and other features.